Introduction

In 1926, the Minister for Finance set up a special committee of persons with artistic knowledge to advise on the designs and he chose Senator W. B. Yeats to chair it.

At the first meeting of the committee, on the 17th June 1926, Joseph Brennan (at that time Secretary to the Department of Finance and later Chairman of the Currency Commission) said that he “wished to convey to the Committee three provisional decisions which had been arrived at by the Minister for Finance in regard to the coins, but which were not to be regarded as the final decisions of the Minister or the Government, or as binding on the Committee.”

These three conditions were :-

- That a harp should be shown on one side of the majority of the coins, if not on all.

- That the inscription should be in Irish only. He also suggested “they consider the utility of having the denomination of the coin shown by means of a numeral, for the assistance of persons unfamiliar with Irish.”

- That no effigies of modern persons should be included in the designs.

After much internal debate and deliberation, Yeats declared that they

“decided upon birds and beasts, the artist, the experience of centuries has shown, might achieve a masterpiece, and might, or so it seemed to use, please those that would look longer at each coin than anybody else, artists and children. Besides, what better symbols could we find for this horse riding, salmon fishing, cattle raising country?“

1928 Irish Free State proof set in case – blue interior

The result was the much acclaimed ‘farmyard set’ of coins that went on to influence international coin design for many decades to come. The proposed new ‘ten shilling’ commemorative coin for 1966 would break most of these conventions.

The Golden Jubilee of the 1916 Easter Rising

The timing of the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising was significant.

- Taoiseach, Seán Lemass, was anxious to secure Ireland’s future within the European Economic Community (EEC) and had attempted to improve relations with both Britain and Northern Ireland.

- He constantly brought to the fore images and references to ‘modern’ Ireland so that the 50th anniversary commemoration was as much about the act of looking forwards as backwards, requiring a delicate negotiation between tradition and change.

- Nowhere was this more apparent than in how the commemoration was communicated to the youth of Ireland, a group which represented the nation’s future but which had mixed reactions to the lessons of the past.

However, harmony was something that eluded Lemass in 1966 and, like now, the government party, had to contend with negative publicity, disputes over the ownership of the legacy of the Rising and questions over the failures of the independent state.

In particular, the female relatives of the signatories were most strident in their criticism

- Margaret Pearse announced a month before the commemoration that she might bequeath St Enda’s to a religious order rather than to the nation because ‘conditions have changed’

- Tom Clarke’s widow threatened to go public with her anger at the description of Pearse as ‘the first President of the Provisional Government’, with the view that ‘surely Pearse should have been satisfied with the honour of commander-in-chief when he knew as much about commanding as my dog’.

- Most public in their dissent were the sisters of Seán MacDiarmada, who shunned the official commemoration for their brother in Kiltyclougher and were joined by a much larger crowd at an alternative parade in the town, co-ordinated by the National Graves Association.

The politics and personalities of the Rising meant that, 50 years later, educationalists, artists, the Labour movement, Irish language groups and some Republicans were particularly vocal about their sense of betrayal.

Also part of the official programme were :-

- the opening of the Garden of Remembrance

- the opening of Kilmainham Jail Museum

- the unveiling of statues to Robert Emmet and Thomas Davis

Irish Ten Shilling Commemorative Coin

The 50th Anniversary was a huge event and the Central Bank of Ireland was to play its part by producing Ireland’s first commemorative coin.

Ireland 1966 ten shilling commemorative coin – inscribed “Éirí Amach na Cásca 1916”, which translates as “1916 Easter Rising” on the edge.

The ten shilling coin is unique insofar as

- it was the only modern circulated Irish coin (before the introduction of Euro) not to feature the harp on the obverse side

- instead, it featured a portrait of Patrick Pearse the revolutionary IRB man and de facto Commander-in-Chief of the 1916 Easter Rising, further making it unique among Irish coinage in that it is the sole coin to feature the image of anyone associated with Irish history or politics

- it was the first Irish commemorative coin issued by the Irish state

- it was the first Irish modern coin to feature a person

- it was the first official coin to commemorate the 1916 Easter Rising

- it was the first modern Irish coin with a value equal to a banknote

Design

The coin was produced for the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising and commenced circulation on 12 April 1966 and was designed by Thomas Humphrey Paget.

- Obverse:

- The obverse design featured an image of Patrick Pearse, the leader of the Dublin Rising who played such a key role in bringing together the various fighting and propaganda elements of the Rising.

- Reverse:

- The reverse design featured an image of the dying Cú Chulainn, the mythical Irish hero who (mortally wounded) tied himself to a ‘standing stone’ and faced off the army of Queen Maeve of Connacht.

- The figure of Cú Chulainn is a miniature of the statue by Oliver Sheppard, in the General Post Office, Dublin.

- Edge:

- The ten shilling is the only Irish coin to feature an inscription on edge until the Irish euro coins, this is “ÉIRI AMAC NA CÁSCA 1916“, which translates as “1916 Easter Rising”; the inscription was in Gaelic type on a plain edge.

- The correct orientation, when the inscription is read, is for the obverse to be on top

- There is a variety, i.e. reverse facing upwards

- It is not known if this variety is scarcer than the ‘normal’ orientation

- This may be a deliberate design since some ‘boxed pairs’ are known to have been issued (see Proofs below)

- In addition to the ‘reverse facing upwards’ variety, other varieties do exist, i.e. some of the letters of “ÉIRI AMAC NA CÁSCA 1916” are jumbled due to a malfunction in the edging machinery.

- For example:

- ÉIRI AMAC NAÁSCA 1916

- For example:

- The ten shilling is the only Irish coin to feature an inscription on edge until the Irish euro coins, this is “ÉIRI AMAC NA CÁSCA 1916“, which translates as “1916 Easter Rising”; the inscription was in Gaelic type on a plain edge.

Specifications

- The coin was 83.5% silver and 16.5% copper

- It measured 1.2 inches (30 mm) in diameter

- Unusually, the thickness of this coin is uneven, the edge of the coin being thicker than the centre, i.e. it is concave

- It weighed 18.144 grams.

Mintage

- Two million coins were produced

- Several Irish banks packaged the coins in ‘branded’ presentation wallets

- These coins are not ‘proof quality’

- A further 20,000 coins were issued as proofs in special issue cases

- These coins were issued in a green leatherette case with a black felt setting and a white lining – the case is not marked but the interior lining is printed with a black harp

- Proof coins in their cases are generally worth more than loose examples

- A smaller (unknown) number of twin sets were issued in larger but otherwise similar cases which allow an obverse and a reverse to be displayed together

- The twin sets command a small premium over a pair of single cases

- These coins were issued in a green leatherette case with a black felt setting and a white lining – the case is not marked but the interior lining is printed with a black harp

Circulation

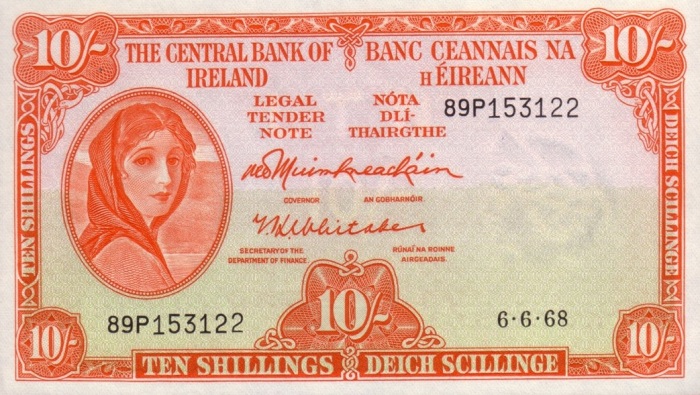

The coin did not prove popular, and 1,270,000 of the two million produced were withdrawn and melted down. Anecdotal evidence at the time suggests that people did not want a coin to replace the equivalent ten shilling banknote – little did they know that the decimal 50p would do so just five years later.

1968 A Series 10s Banknote (6-June-1968)

- The Arab-Israeli War of 1967 caused a sudden increase in the bullion value of silver and this resulted in the coin being worth substantially more than its face value – thus the Central Bank of Ireland was keen to withdraw them from circulation and retain them as specie

- By the time of the Oil Crisis of 1973, the ten shilling coins were fetching as much as 7 times their face value – a 600% profit in 7 years for anyone lucky enough to be able to afford investing in large amounts of them in 1966

Withdrawal

This coin was officially removed from circulation from 10 February 2002, at the time of the conversion to the euro.

Who was Thomas Humphrey Paget?

Thomas Humphrey Paget, OBE (13 August 1893 – May 1974) was an English medal and coin designer and modeller. Paget’s designs are indicated by the initials ‘HP’. Paget was first approached by the Royal Mint in 1936 after the accession of (the soon to be deposed) King Edward VIII.

A measure of the success of the Edward portrait can be seen in the fact that Paget alone was commissioned to design George VI’s effigy in 1937. He is the only artist to have a second obverse design approved for use in sterling coinage in the 20th century. The portrait of George VI has since been described as “the classic coinage head of the 20th century”.

- He was awarded the O.B.E. (Civil) in the King’s Birthday Honours of 1948.

- Paget’s later work included

- an effigy of King Faisal II of Iraq in 1955

- the 1970 Commonwealth Games medal which featured the Duke of Edinburgh

- He also produced an effigy of Queen Elizabeth II for a commemorative Isle of Man issue in 1965

Who was Oliver Sheppard?

Oliver Sheppard, RHA (1865 – 14 September 1941) was an Irish sculptor, most famous for his 1911 bronze statue of the mythical Cuchullain dying in battle. In 1935, his bronze statue of The “Dying Cuchulain” was installed at the GPO, Dublin (the rebels’ headquarters in 1916) at the request of Éamon de Valera, President of the Executive Council (prime minister) at that time.

- The statue has had a continuing impact, and in 1966 a 50th anniversary commemoration special coin was struck with an image of it.

Sheppard was born at Cookstown, Co Tyrone to artisan parents from Dublin, and he was later based in Dublin for almost all of his life, having travelled widely across Europe. His main influence was the Frenchman Edouard Lanteri who taught him at the Royal College of Art in London, and then at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art (DMSA) in Dublin (now the NCAD), where he later became a lecturer. He is best known for the following works :-

- 1901; imaginary statue of “Inis Fáil“, seeing Ireland as an “island of destiny”.

- 1905; statue of a pikeman at Wexford, recalling the rebels in the 1798 rebellion.

- 1908; statue of a pikeman at Enniscorthy.

- 1909; bust of the poet James Clarence Mangan in St Stephen’s Green, Dublin.

- 1911; The “Dying Cuchulain” is Sheppard’s most iconic piece, inspired in part by the success of “Cuchulain of Muirthemne“, the translation by Lady Gregory of most of the Tain saga that was published in 1902.

- 1920; war memorials for the Irish solicitors and barristers who had died in the First World War (1914–18), which includes a bust of Major Willie Redmond.

- 1922, bronze plaque in memory of Dr. James Little at the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland.

- 1926; bust of his lifelong friend George Russell, best known as “Æ”.

- 1930; busts of John Joly at Trinity College Dublin and the Royal Dublin Society.

- 1935; Aida, a bust now at the Crawford Gallery in Cork.

In 1927, Shepphard was one of the artists invited to submit designs for the new Irish Free State coinage. Although Shepphard did not win the design competition, his plaster models are on permanent display at The National Museum of Ireland, Collins Barracks, in Dublin.

Plaster models of some of the Oliver Sheppard patterns for the 1927 coin design competition

Who was Cú Chulainn?

Cú Chulainn is an Irish mythological hero who appears in the stories of the Ulster Cycle, as well as in Scottish and Manx folklore. He is believed to be an incarnation of the god Lugh, who is also his father. His mother is the mortal Deichtine, sister of Conchobar mac Nessa.

- Born Sétanta, he gained his better-known name as a child, after killing Culann’s fierce guard-dog in self-defence and offered to take its place until a replacement could be reared.

- At the age of seventeen, Cú Chulainn single-handedly defends Ulster from the army of Connacht in the Táin Bó Cúailnge.

- Medb, queen of Connacht, has mounted the invasion to steal the stud bull Donn Cúailnge, and Cú Chulainn allows her to take Ulster by surprise because he is with a woman when he should be watching the border.

- The men of Ulster are disabled by a curse, so Cú Chulainn prevents Medb’s army from advancing further by invoking the right of single combat at fords.

- He defeats champion after champion in a stand-off lasting months.

- It was prophesied that his great deeds would give him everlasting fame, but his life would be a short one.

Cú Chulainn’s Death

Medb conspires with Lugaid, son of Cú Roí,Erc, son of Cairbre Nia Fer, and the sons of others Cú Chulainn had killed, to draw him out to his death. Lugaid has three magical spears made, and it is prophesied that a king will fall by each of them.

- With the first he kills Cú Chulainn’s charioteer Láeg, king of chariot drivers.

- With the second he kills Cú Chulainn’s horse, Liath Macha, king of horses.

- With the third he hits Cú Chulainn, mortally wounding him.

Cú Chulainn ties himself to a standing stone to die on his feet, facing his enemies. This stone is traditionally identified as one still standing at Knockbridge, Dundalk, Co Louth.

- Due to his ferocity even when so near death, it is only when a raven lands on his shoulder that his enemies believe he is dead.

Lugaid approaches and cuts off his head, but as he does so the “hero-light” burns around Cú Chulainn and his sword falls from his hand and cuts Lugaid’s hand off. The light disappears only after his right hand, his sword arm, is cut from his body.

Sheppard’s image of the death of the mythic warrior hero Cúchulainn in the re-constructed GPO was meant to link cultural nationalism to political independence, “dying for Ireland”

Related Articles

Irish Pre-Decimal Coins (1928-1969)

- O’Brien Coin Price Guide: Irish Pre-Decimal Farthing

- O’Brien Coin Price Guide: Irish Pre-Decimal Halfpenny

- O’Brien Coin Price Guide: Irish Pre-Decimal Penny

- O’Brien Coin Price Guide: Irish Pre-Decimal Threepence

- O’Brien Coin Price Guide: Irish Pre-Decimal Sixpence

- O’Brien Coin Price Guide: Irish Pre-Decimal Shilling

- O’Brien Coin Price Guide: Irish Pre-Decimal Florin

- O’Brien Coin Price Guide: Irish Pre-Decimal Halfcrown