Celtic coinage is the most intriguing and varied of all the British coins since no one knows specifically for whom, when or where they were produced. To date, over 45,000 of ancient British and Gaulish coins have been discovered in Britain and all of these have been recorded at the Oxford Celtic Coin Index, but no Celtic coins have been discovered by archaeologists in Ireland.

- They were either struck by hand (or cast) in gold, silver and bronze and used for approximately 150 years

- Both methods required a substantial degree of metallurgical knowledge

- The earliest coins to circulate in Britain c. 150 BC were made in Gaul and are known as Gallo-Belgic A-F

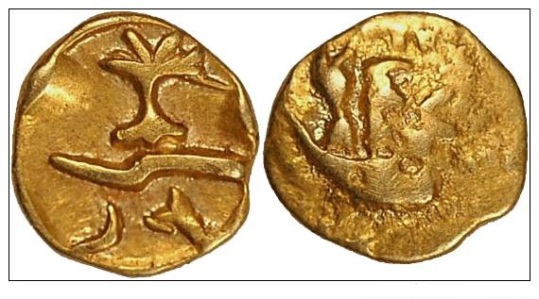

Imported Gallo-Belgic Morini “Geometric type” Gold quarter stater- 1,5 gram, minted 65-50BC obv: tree, zig-zag rev: two persons in a boat

Since the Celts were illiterate in pre-Roman days, it was ancient Greek and Roman authors who first recorded the names of tribes. The famous Geography of Claudius Ptolemy, written in Greek c. 150 AD, and this provides the framework of our knowledge.

- This map doesn’t look anything like what we see in a modern atlas, yet it was revolutionary in its day

- Ptolemy relied on the work of an earlier geographer, Marinos of Tyre, who continually updated his work as new information became available

Ptolomeic maps persisted until well into the Middle Ages, as can be seen by the Cosmographia Claudii Ptolomaei Alexandrini, by Jacob d’Angelo (Reichenbach Monastery) after Claudius Ptolemaeus, in 1467

The Roman conquest of Britain began in 43 AD and this greatly enhanced Roman knowledge of the island. The Romans turned tribes into civitates, with a Roman-style town as a civic centre. Ptolemy gives the names of Roman towns. Yet he retained the old names for the islands:

- Albion for Britain, and Ierne (Latinised as Hibernia) for Ireland.

- The island group had long been known collectively as the Pretanic or Britanic isles.

- As Pliny the Elder explained, this included the Orcades (Orkney), the Hæbudes (Hebrides), Mona (Anglesey), Monopia (Isle of Man), and a number of other islands less certainly identifiable from his names.

- The post-conquest Romans used Britannia or Britannia Magna (Large Britain) for Britain and Hibernia or Britannia Parva (Small Britain) for Ireland

Both the Romans and the Celts initially copied Greek coins and, as their usage spread throughout their respective zones of influence, the coins took on more local designs and features.

- Celtic coinage was minted by the Celts from the late 4th century BC to the late 1st century BC

- Celtic coins were influenced by trade with and the supply of mercenaries to the Greeks, and initially copied Greek designs, especially Macedonian coins from the time of Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great

- It was the Greeks that first described the Celts (or Keltoi) as the ‘wagon, or horse grave’ people

- Coincidentally, there has never been a wagon or horse grave excavated by Irish archaeologists either !

By the time the Romans invaded Britain in AD 43, the indigenous Celtic tribes there had already been producing their own coins for some time. As Roman influence (and domination) grew, the British Celtic coins took on a more Roman character … until only Roman coins remained. The ‘puppet kings’ initially allowed to rule were gradually replaced by Roman governors as Roman colonisation and ‘Roman-isation’ of the natives became a fait accompli.

- Britain’s first regular home-made Celtic coins were bronze coins copying those of Massalia (Marseilles).

- Made in Cantion (Kent) c.120-100 BC, they circulated alongside gold coins imported from Gaul.

- During the Gallic Wars, 58-51 BC, many other Gaulish coins – gold, silver, bronze – came to Britain

- Some were brought by refugees, whereas others were probably brought back by mercenaries and/or imported by merchants

Celtic Britain – map of coin-issuing tribes superimposed on a modern map. This map clearly shows that only the Celtic tribes in South of modern day England minted their own coins. Three main phases occur: (1) copies of Belgic designs; (2) indigenous British designs; (3) and, later, designs influenced by Roman coins (Latin text / Roman topics).

Below is a list of British tribes that produced their own coinage and a few examples of the beautiful Celtic designs contained within this short-lived, but very exciting coinage. Despite having details of over 45,000 coins on their database – a good sample size by any statistician’s standards – new coins are being discovered on a monthly basis.

The Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) is a voluntary programme run by the United Kingdom government to record the increasing numbers of small finds of archaeological interest found by members of the public. It was founded in 1997 and is primarily focused on private metal detectorists who through their hobby regularly discover artefacts that would otherwise go un-recorded and sold on the black market.

PAS has been a very positive influence on Detecting Clubs around the UK and they are now much better organised, more ‘professional’ in their approach and this has greatly benefited the study of British Celtic coins.

- The PAS Database now incorporates the data held by the Celtic Coin Index, which has been based at Oxford University since 1961.

- This provides an unparalleled resource for the study of Iron Age or Celtic coinage.

- The guide gives you access to over 41,000 examples of Iron Age coins with around 40,000 images of various resolutions.

- It can be accessed at https://finds.org.uk/

In Britain there were five main Celtic denominations which collectors classify as: gold staters, gold quarter staters, silver units, silver minims, and bronze (or potin) units.

- Gold staters were the principle denomination of pre-Roman Britain. The first gold stater made in Britain, the Kentish A, ca. 70-60 B.C., is 19 mm, weighs 6.7 gms

- Gold quarter staters are 8 mm. to 14 mm. in diameter, weigh 1.0 gm to 2.0 gms on average, and are comparatively scarce as a denomination (fewer were minted)

- Silver units are 11mm to 15mm on diameter, weigh about 1.0 gm on average and come in a huge range of designs, mostly copied from contemporary Roman denarii.

- Silver minims are about 8 mm, weigh 0.3 gms and were issued mostly by the Atrebates, ca. 25 B.C.-A.D. 43

- Bronze and potin units, both struck and cast, vary widely in size and weight and are often corroded after 2,000 years in the soil

_________________________________________________

ATREBATES – modern Hampshire, West Sussex and Berkshire, capital Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester)

Atrebates. Eppilus, Kentish Type, 10 BC-10 AD. Gold Quarter Stater. (1.2g). EPPIL COMI, inscription in two lines / Pegasus flying right

The Atrebates (singular Atrebas) were a Belgic tribe of Gaul and Britain before the Roman conquests. They were united with the Regini, under a common king (Comios, or Comminius) but they may have been a disparate group of tribes with little in common with one another – apart from Belgic roots and Comminios. They were also known as the Bear People.

The date at which the Belgic Atrebates arrive in Britain is unknown, but it may not be too long before the arrival of Commius, perhaps no more than a generation or two. They possibly migrate into the country from the south coast (most likely via Selsey in West Sussex, precisely the same point at which the later South Saxons also land).

- Gold

- Atrebates gold stater, c. 55-45 BC, Blank, struck with worn die; Reverse: Disjointed horse right, triple tail, spoked wheel

- Comminius was appointed king of the Atrebates in Gaul in 57 BC by Caesar.

- He was sent to Britain in 55 BC before Caesar’s first expedition to persuade the Britons accept Caesar.

- Instead, Commius was arrested, but was handed back to Caesar when the latter landed.

ATREBATES REGNII – the Red Kings

A secondary, and earlier, capital could be claimed at Noviomagus (Chichester, West Sussex), which belonged to a division of the tribe known as the Regninses. These people were thinly scattered north and south of the Weald and seem to have escaped true conquest or even much influence from the Atrebates. Another tribal centre was at Cunetio (Mildenhall, Wiltshire), probably a pagus.

- After the legate Titus Labienus tried to execute Commius for conspiracy, Commius vowed to never associate with Romans again.

- He eventually fled to Britain, where he was again king of the Atrebates.

- Commius, 57 – c. 20 BC

- Commios, c. 50-25 BC. Gold Stater, E-Type. Wreath pattern with crescents. Extremely rare

- Tincomarus, c. 20 BC – AD 7, son of Commius

- Atrebates. Tincomarus Gold AV Quarter-Stater, c. 25 BC – 7 AD. TINC on rectangular tablet / Head of Medusa

- Eppillus, AD 8 – 15, brother of Tincomarus

- Epillus. Mid-late 1st century BC Silver Unit. REX CALLE above and beneath crescent / EPP, eagle flying right

- Verica, 15 – 40, brother of Eppillus

- Verica, c. AD 10-40. Gold Stater, vine leaf type. Extremely fine.

- Commius, 57 – c. 20 BC

- He eventually fled to Britain, where he was again king of the Atrebates.

BELGAE – Wiltshire and Hampshire, capital Venta Belgarum, or ‘market place of the Belgae’ (Winchester)

According to classical authors, they were a different people and spoke a different language from the Gauls and Britons; they were clearly an Indo-European people and may have spoken a Celtic language, although there is a remote possibility that their language may have been Pre-Celtic Indo-European; they dwelt in Belgica, parts of Britannia, and may have dwelt in parts of Hibernia and also of Hispania – a well-travelled group that seemed to have ‘settled’ in many places. Perhaps they were refugees from wars and suffered periodic displacement.

Coins of the Belgae are scarce, and some (like the one’s illustrated below) are exceedingly rare.

- Gold

- Hayling Wreath gold quarter stater, c.50-30 BC – the only other known example is plated

- Basingstoke Wreath gold quarter stater, c.50-30 BC – only one other example recorded

- Cheriton Wheel gold stater, 50-10 BC – extremely rare

- Belgae(?). Uninscribed gold stater, c. 65 BC-AD 45. British B–Chute type

- Silver

- Danebury Spear silver unit, c.50-30 BC – only three other examples known

- Drayton Dragons silver unit, c.50-30 BC – only three other examples recorded

CANTIACI – Kent, capital. Durovernum Cantiacorum (Canterbury)

Cantii. Dubnovellaunus. c 30-10 BC. Silver Unit. Winged beast standing right, annulets around, Horse standing left

The Cantiaci or Cantii were an Iron Age people living in Britain before the Roman conquest, and gave their name to a civitas of Roman Britain. The area is now called Kent, in south-eastern England and they were also known as the Clear Water People. They were bordered by the Regnenses to the west, and the Catuvellauni to the north. Julius Caesar landed in Cantium in 55 and 54 BC, the first Roman expeditions to Britain.

- Gold

- Cantiaci (c.50-30 BC), gold Stater, late Weald net, blank, rev. horse left annulet on chest

- Cantii, gold quarter stater, early Trophy type, c. 45-40 BC, plain obverse, rev. stylised Roman trophy

- Cantii, uninscribed coinage, c.50 BC, gold Quarter Stater, rev. stylised Roman trophy

He recounts in his De Bello Gallico v. 14:

- “Of all these (British tribes), by far the most civilised are they who dwell in Kent, which is entirely a maritime region, and who differ but little from the Gauls in their customs”

Caesar mentions four kings, Segovax, Carvilius, Cingetorix and Taximagulus, who held power in Cantium at the time of his second expedition in 54 BC. The British leader Cassivellaunus, besieged by Ceasar in his stronghold north of the Thames, sent a message to these four kings to attack the Roman naval camp as a distraction. The attack failed, a chieftain called Lugotorix was captured, and Cassivellaunus was forced to seek terms.

In the century between Caesar’s expeditions and the conquest under Claudius, several kings in Britain began to issue coins stamped with their names. The following kings of the Cantiaci are known:

- Dubnovellaunus may have been an ally or sub-king of Tasciovanusof the Catuvellauni, or a son of Addedomarus of the Trinovantes. Presented himself as a supplicant to Augustus 7 BC.

- Cantii. Dubnovellaunus. c. 30-10 BC. Silver Unit, Winged beast standing right / Horse standing left

- Vosenius, (Vosenos, Vodenos) ruled between 10 BC and c. 5 to 15 AD.

- Vodenos Dragons silver unit, c.10 BC-AD 5 – a new type, previously unrecorded

- Eppillus, originally king of the Atrebates. Coins indicate he became king of the Cantiaci c. 15 AD, at the same time as his brother Verica became king of the Atrebates.

- Eppilus, Kentish Type, 10 BC-10 AD. Gold Quarter Stater EPPIL COMI, inscription in two lines / Pegasus flying right

- Cantii. Eppilus, Kentish Type, 10 BC-10 AD. winged victory

- Cunobelinus, king of the Catuvellauni who expanded his influence into Cantiaci territory.

- see Catuvellauni coins below

- Adminius, son of Cunobelinus. Seems to have ruled on his father’s behalf, beginning c. 30 AD. Suetoniustells us he was exiled by Cunobelinus c. 40 AD, leading to Caligula’s aborted invasion of Britain.

- Fragment of an Iron Age silver unit of Amminus (probably Adminius), probably struck in Kent circa AD 38-40

- Anarevitos, known only from a coin discovered in 2010, probably a descendant of Eppillus and ruling c. 10 BC – 20 AD

- Anarevitos gold stater Cantii (South Eastern)

CATUVELLAUNI – north Thames, capital. Verlamion (St. Albans)

Catuvellauni & Trinovantes. Cunobelin, c. 8-41. Stater Gold, Camulodunon (Colchester). CAMVL + Two horses galloping

The Catuvellauni were a tribe or state of south-eastern Britain before the Roman conquest, attested by inscriptions into the 4th century. The fortunes of the Catuvellauni and their kings before the conquest can be traced through numismatic evidence and scattered references in classical histories. The extensive earthworks at Devil’s Dyke near Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire are thought to have been the tribe’s original capital.

Cassivellaunus, who led the resistance to Julius Caesar’s first expedition to Britain in 54 BC, is often taken to have belonged to the Catuvellauni. His tribal background is not mentioned by Caesar, but his territory, north of the Thames and to the west of the Trinovantes, corresponds to that later occupied by the Catuvellauni. Cassivellaunus is not known to have minted coins.

Tasciovanus was the first king to mint coins at Verlamion, beginning ca 20 BC. He appears to have expanded his power at the expense of the Trinovantes to the east, as some of his coins, ca 15–10 BC, were minted in their capital (Colchester).

- Tasciovanus, c. 20 BC – AD 9

- Tasciovanus Silver Unit. ca 25-20 BC. First coinage, Verulamium. VER in pellet ring / Celticized horse right

- Tasciovaunus Gold Quarter Stater, TASC in tablet on vertical wreath / Pegasus galloping left, tail raised

- Tasciovanus Bronze Unit. ca 10 BC – 10 AD. Lion right / Eagle with spread wings standing right, head left

- Cunobelinus, AD 9 – AD 40

- Cunobelin (early 1st century AD), Stater, linear type, c.AD 10-20. CA-MV either side of corn-ear / CVN, celticised horse

- Cunobelin. c. AD 10-43. Gold Quarter Stater, Biga type. Camulodunum mint. First issue. CAMVL (ligate) on central panel

- Cunobelin. c. 20-43 AD. Silver Unit, de Jersey type D7. CVNOBELINVS, female head right / TASCIO, Victory standing right

- Cunobelin. c. 10-43 AD. Bronze Unit struck ca AD 10-15. Coiled serpent with ram’s head within bezeled border

- Togodumnus

- Caratacus

- Iron Age silver unit of Caratacus, ruler of the Catuvellauni until c. AD 51

TRINOVANTES – Essex, S. Suffolk, capital. Camulodunon (Colchester)

Trinovantes. Tasciovanos, c. 25 BC – AD 10. Stater (Gold). TASCI RICON within double panel over vertical wreath

The Trinovantes or Trinobantes were one of the Celtic tribes of pre-Roman Britain. Their territory was on the north side of the Thames estuary in current Essex and Suffolk, and included lands now located in Greater London. They were bordered to the north by the Iceni, and to the west by the Catuvellauni. Shortly before Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain in 55 and 54 BC, the Trinovantes were considered the most powerful tribe in Britain. At this time their capital was probably at Braughing (in modern-day Hertfordshire).

- Cassivellaunus,

- Addedomarus, who took power c. 20-15 BC, and moved the tribe’s capital to Camulodunum

- Trinovantes. Andoco, c. 20-1 BC. Gold Stater, Crossed wreaths + Horse prancing to right

- Celtic stater of Addedomaros 37 – 33 BC

- Addedomaros, Gold Stater, Crossed wreaths with two crescents ‘back to back’

Addedomaros was the last Trinovantian king and his remains are possibly buried in the Lexden Tumulus close to Gosbecks. The king who was buried here had been ritually burned along with his goods that were a mixture of Celtic and Roman artefacts. Among them were the fragments of a small casket and inside was a medallion bearing the head of the Emperor Augustus.

- Addedomarus was briefly succeeded by his son Dubnovellaunus c. 10–5 BC

- Trinovantes. Dubnovellaunos, c. 5 BC – AD 10. Gold Stater. Wreath design with crescents at the middle

The Trinovantes were conquered by either Tasciovanus or his son Cunobelinus (both minted coins in their capital, Colchester) but re-appear in history when they participated in Boudica’s revolt against the Roman Empire in 60 AD. Their name was given to one of the civitates of Roman Britain, whose chief town was Caesaromagus (modern Chelmsford, Essex). The style of their rich burials (see facies of Aylesford) is of continental origin and evidence of their affiliation to the Belgic people.

CATUVELLAUNI & TRINOVANTES – united by Cunobelinus and/or his son, Tasciovanus (from 1 BC to c. 40 AD)

Catuvellauni & Trinovantes. Cunobelin, c. 8-41. Stater (Gold), Camulodunon (Colchester). CVN Horse jumping to right

- Gold

- Catuvellauni & Trinovantes. Cunobelin, c. 8-41. Gold Stater, first issue, Camulodunon (Colchester)

- Catuvellauni & Trinovantes. Cunobelin, c. 8-41. Gold Stater, CVN Horse jumping to right

- Catuvellauni & Trinovantes. Tasciovanos, c. 25 BC – AD 10. Gold Stater, Warrior series B / Crossed wreath motif

- Catuvellauni & Trinovantes. Tasciovanos, c. 25 BC – AD 10. Gold Stater, TASCI / RICON within double pane

- Silver

- Bronze

- Trinovantes & Catuvellauni. Cunobelin. Bronze Unit, struck c. 20-43 AD. Male bust right

- Catuvellauni & Trinovantes. Cunobelin. c. 10-41 AD. Bronze Unit, Sow Type

CORIELTAVI – East Midlands, from Humber to Welland. Capital: Ratae Corieltauvorum (Leicester)

The Corieltauvi (formerly thought to be called the Coritani, and sometimes referred to as the Corieltavi) were a tribe of people living in Britain prior to the Roman conquest, and thereafter a civitas of Roman Britain. Their territory was in what is now the English East Midlands, in the counties of Lincolnshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Rutland and Northamptonshire. They were bordered by the Brigantes to the North, the Cornovii to the West, the Dobunni and Catuvellauni to the South, and the Iceni to the East.

- The Corieltauvi were a largely agricultural people who had few strongly defended sites or signs of centralised government.

- They appear to have been a federation of smaller, self-governing tribal groups.

- From the beginning of the 1st century, they began to produce inscribed coins:

- almost all featured two names, and one series had three, suggesting they had multiple rulers.

- The names on the earliest coins are so abbreviated as to be unidentifiable.

- The discovery of the Hallaton Treasure more than doubled the total number of Corieltauvian coins previously recorded

- In 2014 26 gold and silver ancient Corieltauvi coins were found in Reynard’s Kitchen Cave

- Gold

- Corieltauvi, Gold Stater, c. 45-10 BC, South Ferriby Type

- CR 18333 Domino. c.45-10 BC. gold stater

- Silver

- South Ferriby. II Type. c.45-10 BC. gold-plated stater

-

Silver unit, Corieltavi, Vep, around AD 30-60. inscription VEPO CORF, possibly “Vep, son of Cor”

Later coins feature the name of Volisios, apparently the paramount king of the region

- Corieltauvi – Volisios Dumnocoveros – Gold Stater, c 35-50 AD Rev: horse left, DVM NOCO VEROS, Very rare

- A copper alloy contemporary copy of an Iron Age coin, imitating a coin attributed to Volisios Dumnocoveros

- Hammered gold stater of the North-Eastern Gold Inscribed ‘VOLISIOS DVMNOCOVEROS’ type (60 BC to 50 BC)

- Inscribed Stater of Volisios Dumnocoveros, Corieltauvi, AD 35-40 issue; Haselgrove Period 3 Phase 8

- Three ‘presumed’ sub-kings include :-

- Dumnocoveros

- Dumnocoveros gold stater, 25-50 AD, vertical wreath with DV to left. Rev: horse left, TIGIR. Rare

- Dumnovellaunus

- <no image – hopefully, coming soon>

- Cartivelios

- <no image – hopefully, coming soon>

- Dumnocoveros

DOBUNNI – Cotswolds, capital. Corinium Dobunnorum (Cirencester)

The tribe lived in the part of southwestern Britain that today broadly coincides with the English counties of North Somerset,Bristol, and Gloucestershire; although at times their territory may have extended into parts of what are now Herefordshire,Oxfordshire, Wiltshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire. Their Territory was bordered by the Cornovii and Corieltauvi to the North; the Catuvellauni to the East; the Atrebates and Belgaeto the South; and the Silures and Ordovices to the West.

Unlike the Silures, their neighbours in what later became south east Wales, they were not a warlike people and submitted to the Romans even before they reached their lands. Afterwards they readily adopted the Romano-British lifestyle. Even though the Dobunni were incorporated into the Roman Empire in AD 43, their territory was probably not formed into Roman political units until AD 96-98. The tribal territory was divided into a civitas centred on Cirencester, and the Colonia at Gloucester. They were also known as the ‘People of the Abyss’.

- Gold

- Dobunni Gold Stater Eisu tree type C, 15-30 AD. Obverse: Dobunnic emblem

- Dobunni, Catti (c.AD 1-20), gold Stater, tree symbol + triple-tailed horse right

- Dobunni 50 BC to AD 50 Comux type, gold Stater, tree symbol + rev. comvx, triple-tailed horse

- Dobunni, Corio (c.20 BC-AD 5), gold Stater, tree-like emblem, rev. co[rio], triple tailed horse right

- Silver

-

Silver unit, Dobunni, Anted, around AD 10-40. stylised head facing right + horse facing left

-

DUROTRIGES – Wessex, capital. Durnovaria (Dorchester)

The tribe lived in modern Dorset, south Wiltshire, south Somerset and Devon east of the River Axe. After the Roman conquest, their main civitates, or settlement-centred administrative units. Their territory was bordered to the west by the Dumnonii; and to the east by the Belgae.

Durotriges were more a tribal confederation than a tribe. They were one of the groups that issued coinage before the Roman conquest, part of the cultural “periphery”, as Barry Cunliffe characterised them, round the “core group” of Britons in the south.

- These coins were rather simple and had no inscriptions

- thus no names of coin-issuers can be known, let alone evidence about monarchs or rulers.

Nevertheless, the Durotriges presented a settled society, based in the farming of lands surrounded and controlled by strong hill forts that were still in use in 43 AD. Maiden Castle is a preserved example of one of these hill forts.

- Gold

- Durotriges. Debased Gold Stater, c. 58-45 BC, Abstract head of Apollo right; Rev: Abstract disjointed horse

- Silver

- Durotriges. Uninscribed. c. 65 BC-AD 45. Silver Stater, Abstract Cranborne Chase type

- Durotriges silver stater, ca 58-35 BC. Abstract head of Apollo right / Disjointed horse left

ICENI – Norfolk, N Suffolk, NE Cambs. Capital, Venta Icenorum (modern-day Caistor St Edmund)

The Iceni or Eceni were a Brythonic tribe in Britannia (or Britain) who inhabited an area corresponding roughly to the modern-day county of Norfolk from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD. They were bordered by the Corieltauvi to the west, and the Catuvellauni and Trinovantes to the south. The tribe turned into a civitas during the Roman occupation of Britannia.

Archaeological evidence of the Iceni includes torcs — heavy rings of gold, silver or electrum worn around the neck and shoulders. The Iceni began producing coins around 10 BC.

- Their coins were a distinctive adaptation of the Gallo-Belgic “face/horse” design

- In some early issues, most numerous near Norwich, the horse was replaced with a boar

- Some coins are inscribed ECENI, making them the only coin-producing group to use their tribal name on coins

The Iceni are, perhaps, the best known Celtic tribe in pre-Roman Britain because of the famous revolt in AD 61 when Boudica led the Iceni and the neighbouring Trinovantes in a large-scale revolt:

- Two cities were sacked, eighty thousand of the Romans and of their allies perished

- The revolt caused the destruction and looting of Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium (London), and Verulamium (St Albans)

- Boudica was finally defeated by Suetonius Paulinus and his legions.

- Although the Britons outnumbered the Romans greatly,

- they lacked the superior discipline and tactics that won the Romans a decisive victory

- Gold

- Iceni, Early Uninscribed Coinage, gold Quarter-Stater, Irstead type

- Iceni, Freckenham Type. Red gold stater 45/40 BC. Trefoil on ornament

- Iceni Gold stater, Norfolk Wolf. Left Type. c.50-15 BC.

- Silver

- Iceni. Mid-Late 1st C BC. Silver Unit. Regular Face/Horse type, attributed to Queen Boudicca

- Iceni silver unit – Uninscribed. c 65-1 BC. Bury Diadem (Gallo-Belgic XD) type

- Iceni silver unit, Antedios D-Bar. c.AD1-20.

- Iceni silver unit, Ecen Corn Ear. c.AD10-43?

- Iceni silver unit, ECE Stepping Horse. c.AD20-43.

- Iceni silver unit, Norfolk God. c.AD25-43

- Iceni silver unit, Norfolk Boar type

______________________________________________________

If you found this article useful, please connect to me on LinkedIn and endorse some of my skills.

Alternatively, please connect or follow my coin and banknote image gallery on Pinterest.

Or, follow me on Twitter (I post daily)

Thank you

Cunobelinus (his Latin name) Cunobelin, British, whose name means ‘Hound of the god Bel ) was devoted to Bel, Biblical Ba’al or Phoenician Bil. Tasiovanus ( or Tax, Taxi etc.) was the Archangel of Bel, a precursor of St Michael and was in charge of the quick and the dead. Prayers to Tascio were common at death, urging Tascio to hasten to the recently buried to take them to Paradise.

This information comes from Prof. Laurence Waddell who wrote, “Makers of Civilization in Race & History”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting! The fact they made and used coins, confirms that the people of southern England already had a materialistic society, trading with the Gauls and the long-distance sea-merchants (the tin traders). So southern England was more advanced at this time than we think … not just primitive, bartering tribes.

I’m reading the new book by James Hawes, “The Shortest History of England” and he says that when Emperor Claudius invaded Britain, in the successful Roman invasion, he was only really interested in the tribes that were minting and using coins (southern England), as he would be able to tax them !

It is always emphasised that the Romans brought many benefits of civilisation to the country. But if we think of what the imperial rulers – based among the trading nations of the Mediterranean – were trying to get for themselves, ie. money and power … then clearly it was always greatly in their interests to encourage a materialistic, status-driven ‘Roman’ culture, was it not ?! The more materialistic the society, the more trade in goods, the more taxes can be levied … !

And we forget that probably most people in the country would not have enjoyed the benefits of hot baths and mosaic floors, just the ruling/trading classes. I do think there was a 2-tier society in Britain in those times, with the immigrant ‘British’ people (the Mediterranean element of ancient Britain) having established themselves as a ruling class over the native Celtic tribes. I suspect that it was these ruling British, and maybe some of the Celtic under-kings, who were enjoying the fashionable Roman villas and life-style, not the majority native Celts … (Check the brilliant research done by Alan Wilson & Baram Blackett into the origins and rulers of ancient Britain.)

LikeLiked by 1 person