Introduction

Hammered coins are produced by hand. This webpage is intended as a catalogue and image library of Irish ‘hammered’ coins, dating from the Hiberno-Norse series to those issued at the time of King Charles I in the mid-17th century.

To find something quickly on this long page, press the Ctrl key + F – a search box will appear on the bottom left of your screen. Type the word you are looking for and click on the down arrow (to go to that word).

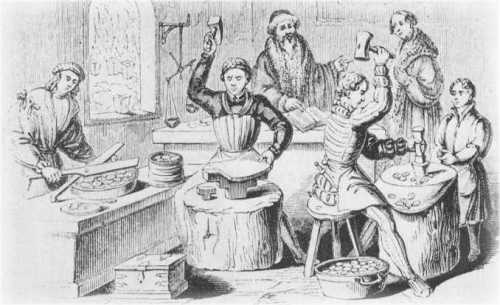

A typical scene at a late medieval mint. The man in the middle is ‘hammering’ designs on to blank pieces of silver or gold. This manual process, known as hammered coinage, proceeded under the management of a moneyer; it was the major method of coin-making from 640 bc until as late as 1662. A moneyer typically kept one of every 16 pieces as his pay, so there is little wonder as to why they rejected the introduction of any mechanical means of coin making until the mid-1600’s.

By way of illustrating what we buy and sell, please link to our Pinterest image pages and/or read the relevant blog posts on Irish numismatic and exonumia topics.

- All of the hyperlinks (in blue) link to a Pinterest image gallery, unless otherwise stated,

- e.g. Blog Post, Coin Guide or Rare Coin Review

- This website is updated on a frequent basis, so do please ‘re-visit’ as often as you can.

Please note: this is a constant “work in progress” and I will be adding more links + more images on an on-going basis. Collectors are quite welcome to send me images of coins that I do not already have, or better images of the one’s I have posted.

The concepts behind this page are as follows :-

- Irish coins are placed in their historical context

- Relevant historical articles will be added to give additional insights into why these coins were issued and/or withdrawn

- The technical details, such as dates, varieties, proofs and patterns are all listed

- Where possible, the multiplicity of commercial or academic reference numbers are correlated and simplified

- We all have a single reference point and image source to share

Where possible, a simplified chronological order has been applied to coins minted in Ireland, minted elsewhere but intended for circulation in Ireland, or (in the instance of the earliest coins) those found in Ireland as a result of trading, gifts, votive offerings, or other forms of transaction.

Ancient Coins

The Kingdom of Lydia existed from about 1200 BC to 546 BC. Coins are said to have been invented in Lydia around the 7th century BC. According to Herodotus, the Lydians were the first people to use gold and silver coins and the first to establish retail shops in permanent locations – their coins were an naturally-occurring alloy of gold and silver, now known as white gold – but called ‘electrum’ by the Ancient Greeks.

Early 6th century BC Lydian electrum coin (one-third stater denomination)

The first coins to be used for retailing on a large-scale basis were likely small silver fractions, Hemiobol, an Ancient Greek coinage minted by the Ionian Greeks in the late sixth century BCE. Eventually, most of the Greek Empire used coins as a means of payment for goods and/or services. The Romans and Celts, in turn copied the Greek coins and gradually imposed their own cultural and commercial inputs to coin design.

-

Image Gallery: Celtic Coins & Artifacts

- Blog Post – What is Celtic Ring Money ?

- Spoiler Alert: Celtic Ring Money isn’t really Celtic; its much older

- Middle Bronze Age: 1500 – 1100 BC

- (Jewellery, not money, but possibly a store of wealth)

- Type 1 – Wire coils

- Irish Coin Daily: Gold Ring (Solid band of gold, thick, oval-sectioned wire that has been coiled three times to produce a spiral ring with simple, unelaborated terminals)

- Type 2 – Double-wire rings

- Irish Coin Daily: Gold Ring – Penannular (Double-wire ring with looped terminals)

- Type 1 – Wire coils

- Late Bronze Age: 1100 – 800 / 700 BC

- (A store of wealth and possibly transactional currency, i.e. proto-money)

- Type 1 – Thin, single-strand of twisted gold with plain, tapering ends

- Irish Coin Daily: Ring Money – Penannular (Twisted, with blunt tapering terminals)

- Irish Coin Daily: Ring Money – Penannular (Cable type, tapering to plain ends) Co Wicklow?

- Irish Coin Daily: Ring Money – Penannular (Plain type) Co Clare?

- Irish Coin Daily: Ring Money – Penannular (Twisted type, ending in globules)

- Irish Coin Daily: Ring Money – Penannular (Thick-walled hollow gold cylinder)

- Irish Coin Daily: Ring Money – Penannular (Band of gold possibly on a bronze core, ribbed decoration around)

- Type 2 – Twisted silver, with a gold-plating or wash

- Type 3 – Two strands of twisted gold soldered together at one point to form a double ring

- Irish Coin Daily: Ring Money – Plain type, double band, square cut at terminals

- Type 1 – Thin, single-strand of twisted gold with plain, tapering ends

The Iron Age is a bit of a misnomer since iron (and iron-working) have their origins in the Bronze Age. Problem was, iron is much heavier and softer than bronze and loses its edge much quicker than bronze. It wasn’t until metalworkers discovered steel (by adding carbon to the smelting process) that the Iron Age came into its own.

-

-

- Iron Age: 800 BC to the Roman invasion of 58 BC (in Gaul)

- Celtic Ring Money

- Iron Age: 800 BC to the Roman invasion of 43 BC (in Britain)

- Celtic Ring Money

- Blog Post – The Enigmatic Coins of the Celtic Tribes of Britain

- Blog Post: Iron Currency Bars from Celtic Britain

- Type 1 – sword-shaped (most common type)

- Sword-shaped bars had a flat, narrow blade 780-890 mm long and weighed between 400-500 g

- They show two common attributes of money: they conform to a weight standard and have a standard, easily recognized appearance

- This variety of bar was used in what would later become the territories of the Corieltauvi, Dobunni, Durotriges and Atrebates

- Type 2 – spit-shaped

- Rare, found in the area later associated with the Dobunni

- Type 3 – bay-leaf shaped

- Rare, known from only a few Cambridgeshire sites

- Type 4 – ploughshares

- Rare, found along the Thames Valley & West Midlands

- Type 1 – sword-shaped (most common type)

- Celtic Ring Money

- Iron Age: 500 BC – 400 AD (in Ireland)

- No Ring Money excavated from a dated Irish Iron Age site (yet?)

- No Celtic coins excavated from a dated Iron Age site (yet?)

- Blog Post – Why have no Celtic coins been found in Ireland ?

- Iron Age: 800 BC to the Roman invasion of 58 BC (in Gaul)

-

Gold Ring Money – Penannular double ring example of circular section with square-cut ends. Believed to have been found in Co Cork. Weight 10.8 g

-

Image Gallery: Roman Coins

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Roman Emperors & their Coins, Part I (Augustus – Nero)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Roman Emperors & their Coins, Part II (Galba – Domitian)

- AD 81, Roman general Gnaeus Julius Agricola gathered an invasion force on the Clyde–Forth line

- Agricola received an Irish prince who had been forced out of Ireland by an internal dispute

- Agricola probably planned to install this Irish chief at Emain Macha, the nearest regia

- Clans of northern Caledonia staged an uprising that threatened the Clyde–Forth frontier

- Agricola suspended his Irish campaign to deal with this new threat

- It took two years to defeat the Highlanders, culminating in the decisive battle of Mons Graupius

- AD 81, Roman general Gnaeus Julius Agricola gathered an invasion force on the Clyde–Forth line

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Roman Emperors & their Coins, Part III (Nerva – Commodus)

- AD 140 Ptolemy’s Geographia provides the earliest known written reference to habitation in the Dublin area, referring to a settlement in the area as Eblana Civitas

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Roman Emperors & their Coins, Part IV (Pertinax – Alexander Severus)

- AD 220 The Annals of the Four Masters, Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, and other semi-historical (non-contemporary) texts, place Cormac mac Airt (226-266) as a longstanding High King of Ireland

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Roman Emperors & their Coins, Part V (Maximinus – Carinus)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Roman Emperors & their Coins, Part VI (Diocletian – Marcian)

- AD 367 The Irish, Picts and Saxons launched a concerted raid on Britain

- AD 378 Niall of the Nine Hostages becomes high king of Ireland

- AD 395 British ask Rome for support against Irish raiders

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Roman Emperors & their Coins, Part VII (Petronius Maximus – Romulus Augustulus)

Trade decayed catastrophically in Western Europe after the fall of Rome. There was a catastrophic drop in urban populations, especially in regions that fell to illiterate successor states. Even in Italy, a large number of Roman towns disappeared after 300 AD, and many others went into deep crisis for several centuries.

- Rome probably lost 90% of its population in the 5th and 6th centuries.

- Hardly any new buildings were constructed anywhere in Italy, and even then the materials were recycled, not new.

In the barbarian kingdoms that followed the Roman Empire, a poor copper-based coinage allowed small-scale transactions, but since the kingdoms had no civil service or bureaucracy, and no paid armies, any gold there was tended to accumulate in hoards (usually the king’s) that were used for major gifts, bribes, and purchases, but did not circulate readily.

- AD 400 St Declan a monk from Wales set up a monastery at Ardmore, in Co Waterford

- AD 407 The Romans begin to withdraw their legions from Britain

- AD 431 Palladius went as bishop to ‘the Irish who believe in Christ’ lands in Wicklow.

- AD 432 St Patrick arrived to convert the kings. Conversion was slow, although St Patrick was not the only missionary. A Gaelic-Christian golden age was to follow.

Western Europe became a region that neither used money nor had any (except in hoards along with other precious objects). Transactions and barter might still be denominated in money, but often the payment was in commodities.

As in the Roman Empire, there was still an imbalance of trace with the East, and this drew gold out of Western Europe that never returned. The last of the barbarians to mint gold coins were the Lombards of Italy, who retained contact with the Byzantine Eastern Roman Empire during their struggle for strategic control of Italy.

- Only in Byzantine-controlled areas such as Sicily were gold coins still used for trade.

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Roman Emperors & their Coins, Part VIII (The Byzantine Empire to AD 800)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Roman Governors of Britain & their Coins

By AD 500, monasticism made strides during this century, influenced by the British church. Monasteries were originally strict retreats from the world, but became wealthy and influential, bearing a rich literary and artistic culture.

- As time passed the monasteries grew into little cities with a variety of inhabitants.

- Provincial kings lived in some of them.

- Some monasteries owned huge tracts of land and were ruled by wealthy abbots.

- In Ireland, some of these monasteries are considered ‘proto-towns’

- They had an internal economy and interacted with their hinterlands

- In England, some abbots even began to issue their own coins

Town life revived only in the 7th century, but only in certain regions that acted as nuclei of trading networks and had retained or regained literacy: France, the Rhineland, and northern Italy. Even then, the political situation in northwest Europe was precarious.

- When the Arabs isolated northwest Europe, the Europeans had to become financially independent.

- From that point, trade in northwest Europe was based on a robust silver coinage, especially the denarius or penny, that was used for 500 years.

Trade routes along the English Channel and North Sea coasts led to the growth of ports that were best placed to channel that trade. Dorestad, on the Rhine 20 km up river from the coast, had been the major city of the dukes of Frisia, then became an important trading center by 680 AD.

Its importance increased greatly as it became the major port of the new Carolingian Empire that Charlemagne carved out from his power base on the lower Rhine. The silver denarius of the Rhine delta was minted by the millions, but its value always followed that of the Islamic dirhem that it imitated in style, size, and name.

Much of the minting was done in Dorestad, especially after Charlemagne’s treaty with the Danes in 782, and his decision in 793 to increase the silver content of the denarius. Frisian traders shipped goods coming down the Meuse and the Rhine from Strasbourg, out of Dorestad all over the Rhine delta, westward along the French coast, eastward via coastal cities such as Emden and Hamburg (Hammaburg) to Denmark and into the Baltic, and northward along the coast of Britain as far as Northumbria.

Dorestad exported pottery, glass, brooches, bronze goods, wine, and silver denarii in exchange for wool, furs, and slaves.

- Offa, the strongest of the Saxon kings in Britain, also minted high-quality silver coins at this time. Charlemagne and Offa entered into a formal trade treaty

- Charlemagne did ship an export of lasting importance to the Saxons in Britain – a currency that had 12 denarii to the solidus and 20 solidi to the pound

- This currency lasted over a thousand years as pounds, shilling, and pence, until it was abolished in 1971.

-

Image Gallery: Anglo-Saxon Coins

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Anglo-Saxon Coins & Their Links to Ireland

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Coinage of the Hiberno-Norse Kingdom of York (AD 920-952)

- List of Viking “Kingdom of York” Coin Finds in Ireland

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Coinage of the Viking Kingdom of Northumbria (AD 921-952)

- List of Viking “Kingdom of Northumbria” Coin Finds in Ireland

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Who Introduced Anglo-Saxon Coins to Ireland and why ?

-

Image Gallery: Islamic Coins

Irish Hammered Coinages

-

Hiberno-Norse Timeline

- Useful links:

- National Museum of Ireland: Viking Age Ireland Resource

- National Museum Northern Ireland: Viking Age Resources

- Jorvik Viking Centre, York: The Jorvik Story

- Useful links:

- 8th Century

- 795 The first Vikings arrived in Ireland, pirates led by aristocrats, raiding Rathlin and Iona

- 9th Century

- 840 Vikings began setting up defended bases and their intensify their raiding

- 841 Dubhlinn (Dublin) begins as a Viking settlement (Dyflin)

- Blog Post: The Viking Settlement at Dublin

- 850 Vikings create the settlement of Waterford

- Blog Post: The Viking Settlement at Waterford

- Blog Post: Artefacts found at the Viking Settlement of Waterford

- 856 Vikings create settlements near Cork

- Blog Post: The Viking Settlement at Cork

- Blog Post: Artefacts found at the Viking Settlement of Cork

- 866 to 876 Vikings from Ireland (Ívarr and Hálfdan) rule at York

- 10th Century

- 902 The Irish attack and drive the Vikings from Dublin into Wales

-

Óttar’s Story – A Dublin Viking in Brittany, England and Ireland, A.D. 902-918 (Stephen M. Lewis)

-

- 914 Large Viking Fleets arrive at Waterford.

- Further settlements built in Limerick and Wexford

- Blog Post: The Viking Settlement at Limerick

- Blog Post: Artefacts found at the Viking Settlement of Limerick

- Blog Post: The Viking Settlement at Wexford

- Blog Post: Artefacts found at the Viking Settlement of Wexford

- Further settlements built in Limerick and Wexford

- 915 Vikings attack Dublin and regain control from the Irish

- 921 Hiberno-Norse Kingdom of Northumbria began to issue its own coins

- Sihtric II Caech. 921-927

- Sitric Cáech died in AD 927

- He was succeeded by Gofraid ua Ímair as king of York

- Gofraid was expelled in the same year by king Æthelstan of England

- Gofraid retreated back to Dublin

- Anlaf Guthfrithsson. 939-941

- In 934, Gofraid ua Ímair died

- He was succeeded by his son, Anlaf Guthfrithsson

- Anlaf captured the king of Limerick, Amlaíb Cenncairech, in 937

- Also in 937, he allied with Constantine II of Scotland in an attempt to reclaim the Kingdom of Northumbria which his father had ruled briefly in 927

- They were defeated by the English king Æthelstan at Brunanburh

- In 939, following the death of Aethelstan, the Vikings under Anlaf Guthfrithsson (a son of Gofraid ua Ímair), re-occupied York

- He left his brother Blácaire mac Gofraid behind to rule in Dublin

- Anlaf Sihtricsson Cuarán. 941-944/5

- Anlaf Guthfrithsson died in 941 and was succeeded in Northumbria by his cousin Anlaf Sihtricsson Cuarán and his son Ragnald Guthfrithsson who seem to have ruled jointly

- After being run out in 944/5, Anlaf returned to York and ruled it alone, from 950-952

- He also issued coins during this, his brief second reign

- Ragnald Guthfrithsson. 941-944/5

- It is uncertain whether Anlaf & Ragnald were co-rulers or rival kings

- They both had coinage – suggesting both ruled at York for a time

- They were both Olaf and Ragnall were driven out of York c. 944/45 by king Edmund of England

- Sihtric II Caech. 921-927

- 976 Brian Boru, king of the Dal Cais, becoming a serious rival to the Uí Neílls.

- Supported by the Ostmen, he conquered Dublin and Leinster, and then the whole country.

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Introduction to the Hiberno-Norse Coinages of the Late 10th & Early 11th C

- 902 The Irish attack and drive the Vikings from Dublin into Wales

- 11th Century

- Image Gallery: 995–1036 Hiberno-Norse – Phase I

- O’Brien Rare Coin Guide: Hiberno-Norse, Phase 1 (AD 995–1022)

- 1002 Brian Boru becomes High King of Ireland

- 1014 Battle of Clontarf (Brian Boru breaks the power of the Vikings)

- 1028 Sihtric builds Christchurch Cathedral & 1st Bishop of Dublin installed

- Image Gallery: 1015–1035 Hiberno-Norse – Phase II

- Vikings begin to assimilate into Irish society

- 1022 Irish High Kings with opposition (constant inter-necine warfare in Ireland)

- King Sihtric and Bishop Dúnán founded Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin

- Image Gallery: 1035–1060 Hiberno-Norse – Phase III

- 1035 Death of Canute: his possessions are divided

- 1035-1040 Harold I, Harefoot, King of England

- 1040-1042 Hardicanute, King of England, dies

- 1042-1066 Edward the Confessor, son of AEthelred II, King of England

- Image Gallery: 1050–1065 Hiberno-Norse – Phase IV

- 1051-1052 Godwin, Earl of Wessex, exiled: he returns with a fleet and wins back his power

- 1052 Edward the Confessor founds Westminster Abbey, near London

- 1053 Death of Godwin: his son Harold succeeds him as Earl of Wessex

- 1054 The Patriarchate of Rome (and the West) falls into schism from the Church

- 1055 Harold’s brother Tostig becomes Earl of Northumbria

- Image Gallery: 1060–1100 Hiberno-Norse – Phase V

- 1063 Harold and Tostig subdue Wales.

- 1066–1087 William I (the Conquerer) invades and conquers England

- Two of Harold’s sons, Godwine and Edmund, fled to Ireland

- Aided by the King of Leinster, Diarmait mac Mail na mBo, they invaded Devon in 1068

- Aided by the Viking fleet of Dublin, they raided Cornwall as late as 1082

- 1087–1100 William II (consolidates Norman rule in England and extends it to Wales)

- 1095 (November 27) Pope Urban II called for a crusade to help the Byzantines and to free the city of Jerusalem

- The armies that left before that time are considered part of the People’s Crusade, i.e no kings took part

- 1097 The crusaders in Constantinople riot after the Byzantine emperor Alexius I Comnenus cuts off their food supplies for refusing swear allegiance to him

- 1099 Crusaders take Jerusalem

- The armies that left before that time are considered part of the People’s Crusade, i.e no kings took part

- Image Gallery: 995–1036 Hiberno-Norse – Phase I

- Image Gallery: 1100–1130 Hiberno-Norse – Phase VI

- 1100–1135 Henry I (seized the English throne after his brother William’s mysterious death)

- Image Gallery: 1130–1150 Hiberno-Norse – Phase VII

- 1135–1154 Stephen & Matilda (civil war in England)

- 1145 Pope Eugenius III issued an appeal for the Second Crusade (1145-49)

- The initial campaigns in Iberia (to expel the Moors) were successful

- The Baltic campaign (against the pagan Wends) achieved little

- The prestigious campaign to re-capture Jerusalem was a disaster

- The two armies lacked discipline, supplies and finance, and both were badly mauled by the Seljuk Turks as they crossed Asia Minor

- When the remaining crusaders laid siege to Damascus, they retreated after only four days – thus ended any further appetite for crusading

Hiberno-Manx Coinage

- Image Gallery: Hiberno-Manx Coins

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Introduction to the Hiberno-Manx Coinages of the mid-11th Century

Hiberno-Saxon Coinage ???

The enigmatic O’Neil REX coin (Parsons, 1921) – is this the first native Irish coin ever struck in Ireland ? This coin was unique for almost a century but recently, another (similar) one has been found. Is this evidence that a native Irish king attempted to mint his own coins ? Were the native Irish also contemplating a currency, or were these coins for other purposes?

- O’Brien Rare Coin Review: Did a Gaelic king mint coins in 11th C Ireland ?

Anglo-Norman Coinages

William the Conquerer famously invaded England in the year 1066 and thereafter set about replacing the old Anglo-Saxon (and Anglo-Norse) ruling class. The Normans didn’t colonise England, they merely took over the management of the country by installing new lords operating a European ‘feudal system’ of service and taxation. This took time to do and many local lords had to be defeated / removed before this process was complete.

- Blog Post: The Norman Invasion of England under William I (the Conquerer)

- Blog Post: Consolidation of Norman Rule in England

- Blog Post: The Anarchy of the Reign of Stephen in England

They didn’t, however, turn their attention to Ireland for over a hundred years. By the time Henry II arrived in 1172, the economic power of the Viking traders had waned and their coinage (not now traded internationally) had degraded to such an extent, that Ireland was a ‘coin-less’ country more or less self-sufficient with few imports/exports and ripe for economic development – provided they could take it and control it !

Henry II led an expedition to Ireland in 1172 and five years later he gave the title of Lord of Ireland to his son, Prince John, who introduced a new coinage for Ireland in his own name – not of his father. Shortly afterwards, a Norman lord (John de Courcy) dared to issue his own. This was the first in a long lineage of Anglo-Norman coinage for Ireland.

House of Anjou

Henry II and Thomas Becket (from an illustrated medieval manuscript). Henry II issued coins in his own name in England and in France, but not Ireland. Unusually for the time, his son (Prince John, Lord of Ireland) and his most powerful knight (John de Curcy, Lord of Ulster) issued coins in Ireland.

- 1154–1189 Henry II (minted no coins in his own name for use in Ireland)

After almost 20 years of civil war in England, including rebellions in Wales and Scottish invasions, Henry II inherited a desolate land and began the long period of reconstruction in England. Henry, also known as Henry Curtmantle (French: Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress or Henry Plantagenet. He ruled as Count of Anjou, Duke of Normandy, and as King of England (1154–1189) and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland, eastern Ireland, and most of western France. This was known as the Angevin Empire but Henry did not attempt to unify the coinages of his scattered dominions, preferring to allow the issue of local coins. Henry II issued no coins in Ireland under his own name but his son (John, Lord of Ireland) and his lord deputy (John de Courcy) each issued coinages.

- Blog Post – The Cambro-Norman Incursion into Ireland (1169-70)

- Blog Post – The Anglo-Norman Invasion of Ireland by Henry II (1172)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Why did Henry II not issue coins under his own name for Ireland?

- Blog Post – The Economic Exploitation of Ireland by European Religious Orders

- Blog Post – The Activities of the Italian Merchant Bankers in Ireland

- Image Gallery: 1177–1189 John (as Lord of Ireland)

- O’Brien Rare Coin Review: John, Lord of Ireland, 1179 (First Profile Issue)

- Blog Post – John’s First Expedition to Ireland (1185)

- Image Gallery: 1185-1195 John de Courcy (Lord of Ulster)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The First Coinage of John de Courcy, Lord of Ulster & Connacht, 1185

- Image Gallery: 1177–1189 John (as Lord of Ireland)

Richard the Lionheart (above) and John Lackland from Thomas Walsingham’s Golden Book of St Albans (1380). Richard, like his father Henry II, issued no coins in his own name for Ireland but his brother (Prince John, Lord of Ireland) and his father’s most powerful knight in Ireland (John de Curcy, Lord of Ulster) did. Richard did, however, issue coins in England, France and Cyprus.

- 1189–1199 Richard I (the Lionheart) (minted no coins in his own name for use in Ireland)

Like his father (Henry II) before him, Richard I did not attempt to unify the coinages of his scattered dominions of the Angevin Empire but continued to allow the issue of local coins. Richard I issued no coins in Ireland under his own name but his brother (John, Lord of Ireland) and his lord deputy (John de Courcy) each issued coinages.

- Image Gallery: 1189–1199 John (as Lord of Ireland)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Second Coinage of John, Lord of Ireland, 1190-98 (Dominus / Cross Potent Issue)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Third Coinage of John Lord of Ireland 1198-99 (Dominus / Cross Pommée Issue)

- Image Gallery: 1195–1205 Ulster (Anonymous Coinage)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Second (Anonymous) Coinage of John de Courcy, Lord of Ulster, 1195

- Blog Post – The Problematic Succession of Richard I

King John presenting a church, painted c. 1250–1259 by Matthew Paris in his Historia Anglorum.

- Image Gallery: 1199–1216 John (as King)

- Blog Post – 1204: John de Courcy expelled from Ireland

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Irish Coinage of King John (REX issue, 1207-11)

- Blog Post – John’s Second Expedition to Ireland (1210)

- Blog Post: The Great Monetary Crisis of 13th C Europe & its effect on the Norman Colony in Ireland

Louis VIII of France briefly ruled about half of England from 1216 to 1217 at the conclusion of the First Barons’ War against King John. On marching into London he was openly received by the rebel barons and citizens of London and proclaimed (though not crowned) king at St Paul’s Cathedral. Many nobles, including Alexander II of Scotland for his English possessions, gathered to give homage to him.

In signing the Treaty of Lambeth in 1217, Louis conceded that he had never been the legitimate king of England. None of this appears to have affected Ireland but it serves to illustrate how tenuous the hold on the English crown was at this time

House of Plantagenet

Henry III re-opened the mint in Dublin and struck a coinage of the same standard as the contemporary English coinage and very similar in appearance to it – its purpose was to provide a convenient mechanism for exporting the silver from Ireland but, unlike John’s REX coinage and previous coinages, no smaller denominations were produced to support the local economy.

- Image Gallery: 1216–1272 Henry III

- 1270-71 Famine in Ireland

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Introduction to the Irish Coinage of Henry III (1216-1272)

Early fourteenth-century manuscript initial showing Edward and his wife Eleanor. The artist has perhaps tried to depict Edward’s blepharoptosis, a trait he inherited from his father

-

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The 1st Irish Coinage of Edward I (1276)

- 1277 Rebellion of Llewelyn ap Gruffydd, prince of Wales

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The 2nd Irish Coinage of Edward I (1280-83)

- 1282-83 Rebellion of David ap Gruffydd in Wales

- 1283 Most of Dublin burned down by an accidental fire

- 1290 Edward’s wife Eleanor died

- 1291 Muslim armies capture Acre, the last Christian holdings in Palestine

- 1292 John Balliol becomes Edward I’s puppet-king, ruling Scotland but collaborating with England

- Economically the wider Anglo-Norman colony in Ireland reached its zenith between 1292-4, when the exchequer was returning around £9,000 per year

- Drogheda – largest walled town

- New Ross – largest port (exporting cattle, hides and wood)

- Dublin – largest urban pop. 10-15,000

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The 3rd Irish Coinage of Edward I (1294-1302)

- 1294 Edward’s possessions in Gascony confiscated by Philippe IV

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The 4th Irish Coinage of Edward I (1294)

- 1294 Famine in Ireland

- Records in Christchurch Cathedral, Dublin recorded that the poor in the city were eating the bodies of executed criminals to survive

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The 5th Irish Coinage of Edward I (1295)

- 1296 Edward invades Scotland and defeats John Balliol at Dunbar

- 1297 Edward regains Gascony from the French

- 1298 Edward defeats William Wallace at Falkirk

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The 6th Irish Coinage of Edward I (1300)

- 1305 Wallace returns to Scotland and is captured

- 1306 Rebellion in Scotland, led by Robert Bruce

- Economic downturn in Norman Ireland – exchequer receipts 1306-07 down to £5893

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The 1st Irish Coinage of Edward I (1276)

- Image Gallery: 1272–1307 Edward I

King Edward II of England was one of history’s least loved monarchs. From the day he took up rule of his nation in 1307 he was controversial due to his strong attachment to a series of court favourites, believed by most to be his lovers. He was also unfortunate in the wars against Scotland, which his father Edward I, ‘Longshanks’ or ‘The Hammer of the Scots’, had started with great success. During his reign not only did the Scots reclaim most of their country from English rule, but a number of civil wars broke out when English Barons rebelled with the purpose of eliminating Edward’s favourites.

- 1307–1327 Edward II (minted no coins in his name for use in Ireland)

- 39% of the taxes levied in Ireland were used to build a chain of castles in Wales

- 1315-18 Edward the Bruce’s Invasion of Ireland

- Damage to the city of Dublin was valued at around £10,000

- 1315-18 Famine in Ireland

- Diseases, famine, murder, and incredible bad weather… Corpses eaten, women eat their children… Wheat 40 shillings a crannoc and in some places 4 marks and more a crannoc… ‘do ithdais na daine cin amuras a cheli ar fod Erenn (and undoubtedly men ate each other throughout Ireland)’

- 1320s devastating economic depression caused by a cattle murrain

A medieval miniature of Edward III of England. The king is wearing a blue garter, of the Order of the Garter, over his plate armour.

-

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Rare Irish Coinage of Edward III (1339-40)

- Image Gallery: 1327–1377 Edward III

- 1327 Almost half of colonised land in Ireland belonged to absentees and the resident Anglo-Irish nobility accused them of endangering the colonies through neglect.

- 1330-31 Famine in Ireland

- 1339 All the corn of Ireland destroyed: general famine

- 1348-50 The Black Death Kills 40-50% of the urban population of Ireland

- 1351 Statute of Labourers

- 1354 Statute of Staples

- 1366 Statutes of Kilkenny, aimed at preventing settlers becoming “too Irish”

- Image Gallery: 1327–1377 Edward III

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Rare Irish Coinage of Edward III (1339-40)

- 1377–1399 Richard II (minted no coins in his name for use in Ireland)

Following the death in 1376 of his father, Edward of Woodstock (the Black Prince), Richard became heir to his grandfather, King Edward III of England, whom he succeeded in 1377 at the age of ten.

- Blog Post – Monetary Crisis (1369), as Richard II orders his colonists in to search for new silver and gold mines in Ireland.

- His reign of twenty-two years saw a number of domestic crises, from the Peasants’ Revolt (1381) to later conflicts with a disaffected nobility, culminating in his usurpation by his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke (crowned Henry IV).

- Richard II was the first English king to visit Ireland since King John in 1210 and the only English monarch to have visited Ireland twice, despite nearly losing his life on the first expedition

- He was deposed in September 1399 by Henry of Bolingbroke

- He died in captivity at Pontefract Castle in February 1400

- Blog Post – Richard II’s first expedition to Ireland (1394-95)

- Blog Post – Richard II’s second expedition to Ireland (1399)

- Famine—summer and autumn windy, wet and cold

The so-called Wars of the Roses was an ‘extended’ civil war over the throne of England fought among the descendants of King Edward III through his five surviving adult sons. Each branch of the family had competing claims through seniority, legitimacy, and/or the gender of their ancestors.

- Edward, the Black Prince (b.1330 d.1376), Duke of Cornwall, Prince of Wales

- William (b. 1335 d.1335), he was buried at the cathedral of York

- Lionel of Antwerp (b.1338 d.1368), Duke of Clarence

- John of Gaunt (b.1340 d.1399), Duke of Lancaster

- Edmund of Langley (b.1341 d.1402), Duke of York

- Thomas (b.1347 d.1347)

- William (b.1348 d.1348)

- Thomas of Woodstock (b.1355 d.1397), Duke of Gloucester

- 1399–1413 Henry IV (Lancaster) (minted no coins in his name for use in Ireland)

HENRY V, King of England, son of King Henry IV by Mary de Bohun, was born at Monmouth, in August 1387. On his father’s exile in 1398, Richard II took the boy into his own charge

- 1413–1422 Henry V (Lancaster) (minted no coins in his name for use in Ireland)

Henry VI was King of England from 1422-1461 and again from 1470-1471, and disputed King of France from 1422-1453. Until 1437, his realm was governed by regents.

Henry VI’s reign over Ireland proved to be rather problematic from a monetary view and he made several proclamations re money supply, foreign exchange and the export of coin.

- Monetary Crisis in Ireland

- Blog Post: Monetary Crisis in Ireland, as Henry VI struggles to with money supply and fiscal control

- Blog Post: Monetary Crisis (1460), as Henry VI fixes exchange rates for foreign coins in Ireland

- Blog Post: Henry VI orders a separate, de-valued currency be made for Ireland (1460)

- O’Brien Rare Coin Guide: The O’Reilly Money (1447-59)

- Blog Post: Edward IV issues Irish coins of the English standard (1463)

- Blog Post: Edward IV issues Irish coins of a lower standard (1467)

- Blog Post: Monetary Crisis (1476), as Edward IV fixes exchange rates for foreign coins in Ireland

- Image Gallery: 1461–1470 Edward IV (York, first reign)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The 1st Series of the Irish Coinage of Edward IV (1461-70)

- Image Gallery: 1471–1483 Edward IV (York, second reign)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The 2nd Series of the Irish Coinage of Edward IV (1471-83)

- Image Gallery: 1461–1470 Edward IV (York, first reign)

- 1483 Edward V (York) (one of the ‘Princes in the Tower’ – no coins ever minted)

- The “Princes in the Tower” is an expression frequently used to refer to Edward V of England and Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York – the only sons of Edward IV of England and Elizabeth Woodville surviving at the time of their father’s death in 1483.

- Then 12 and 9 years old, they were lodged in the Tower of London by the man appointed to look after them, their uncle & Lord Protector: Richard, Duke of Gloucester.

- This was supposed to be in preparation for Edward’s coronation as king but Richard took the throne for himself and the boys mysteriously disappeared.

- The “Princes in the Tower” is an expression frequently used to refer to Edward V of England and Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York – the only sons of Edward IV of England and Elizabeth Woodville surviving at the time of their father’s death in 1483.

- Image Gallery: 1483–1485 Richard III (York)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Irish Coinage of Richard III (1483-1485)

House of Tudor

- Image Gallery: 1485–1509 Henry VII (of Lancastrian descent, via John of Gaunt)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: Introduction to the Irish Coinage of Henry VII (1485-1505)

- The First Coinage of Henry VII (1483-1490)

- Lambert Simnal initially claimed to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, the younger son of King Edward IV but later claimed to be Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick

- 1487 Lambert Simnal (Yorkist Pretender, crowned as Edward VI in Dublin)

- The Second Coinage of Henry VII (1488-1490)

- 1491 Perkin Warbeck claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, having supposedly escaped to Flanders.

- Warbeck’s claim was supported by some contemporaries (including the princes’ aunt, Margaret of York)

- Richard IV ?

- 1491 Perkin Warbeck claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, having supposedly escaped to Flanders.

-

- The Third Coinage of Henry VII (1496-1505)

- Image Gallery: 1509–1547 Henry VIII

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Irish Groats & Half-Groats of Henry VIII (1530-38)

- Image Gallery: 1547–1553 Edward VI

- 1553–1554 Mary I (alone)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Irish Coinage of Mary I (1553-54)

Mary did not believe that she should marry one of her own subjects. She thought that a good Christian wife should not be able to lord over her husband as she would be forced to do. She would have to marry someone of equal status as her, and she would not allow him to rule over England. The person she chose was Philip II of Spain, who was the son of her cousin, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. This has been seen as the defining mistake of her reign.

- Image Gallery: 1554–1558 The Irish Coins of Philip & Mary

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Irish Coinage of Philip II & Mary I (1554-58)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: An Introduction to the Irish Coinage of Elizabeth I

- Image Gallery: 1558–1603 The Irish Coins of Elizabeth I

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The First Irish Coinage of Elizabeth I (1558)

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Second Irish Coinage of Elizabeth I (1561)

- Blog Post: Monetary Crisis (1586), as Elizabeth I prorogues counterfeit gold or silver coins of other realms in Ireland

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Third Irish Coinage of Elizabeth I (1601-02)

House of Stuart

The reign of James I (pictured above) was somewhat of a transition period in Irish numismatic history for he was the last English monarch to issue ‘hammered’ coins (produced by hand) for Ireland and also the first to issue ‘milled’ coins, i.e. manufactured by machine. His ‘milled’ coins were not intended to be used in Ireland but a later version of his ‘patent’ farthings were ‘authorised for use’ in Ireland – although they were struck for his son, Charles I, from 1622 onwards.

- Image Gallery: 1603–1625 – The Irish Coins of James I

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The First Irish Coinage of James I

- O’Brien Coin Guide: The Second Irish Coinage of James I

_____________________________________

If you have any queries regarding Irish hammered coins, please email us on

old.currency.exchange@gmail.com

____________________________________________________________

If you found this website useful, please connect to me on LinkedIn and endorse some of my skills.

Alternatively, please connect or follow my coin and banknote image gallery on Pinterest.

Or, follow me on Twitter (I post daily)

Thank you

This is a fantastic source of information. thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike

Pingback: Acknowledgements – hENRICVS.com